Client story

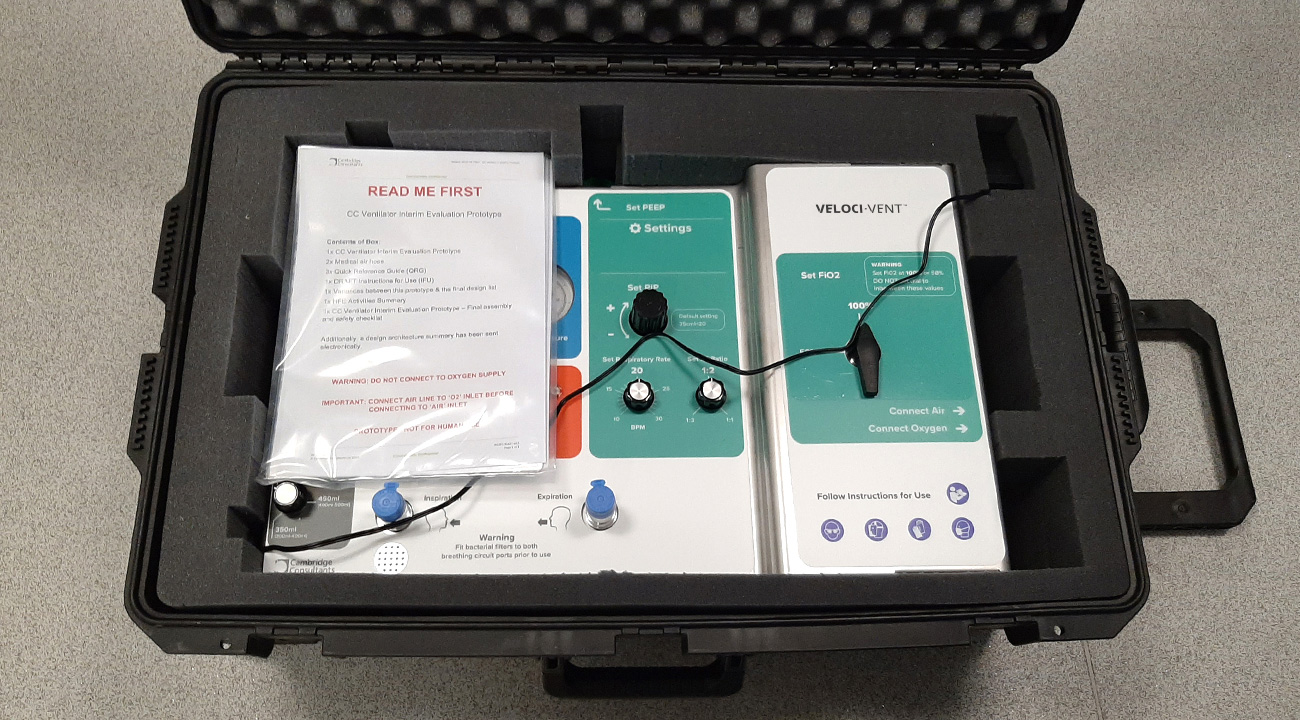

The call from the UK Government came in the late afternoon of Friday the 13th of March. Faced with the biggest health crisis in living memory, there was a risk that the nation’s ventilator capacity would be overwhelmed. This is the story of our response: Veloci-Vent, a sophisticated ventilator created from scratch in a little over six weeks.

Proud to help

Cambridge Consultants was proud to assist in the rapid development and manufacture of ventilators to meet the unprecedented challenge faced by NHS hospitals. To help deal with the coronavirus pandemic, the government’s Ventilator Challenge involved multiple concurrent streams. Leading technology and engineering firms were engaged to build existing, modified or newly designed ventilators at speed.

Life-saving equipment

The government was faced with an unacceptable worst-case scenario of not having enough capacity of life-saving equipment. Our project delivered a viable option, which fortunately was not needed as infection rates were brought under control. The design remains available, should the need arise in the future.

Committed response

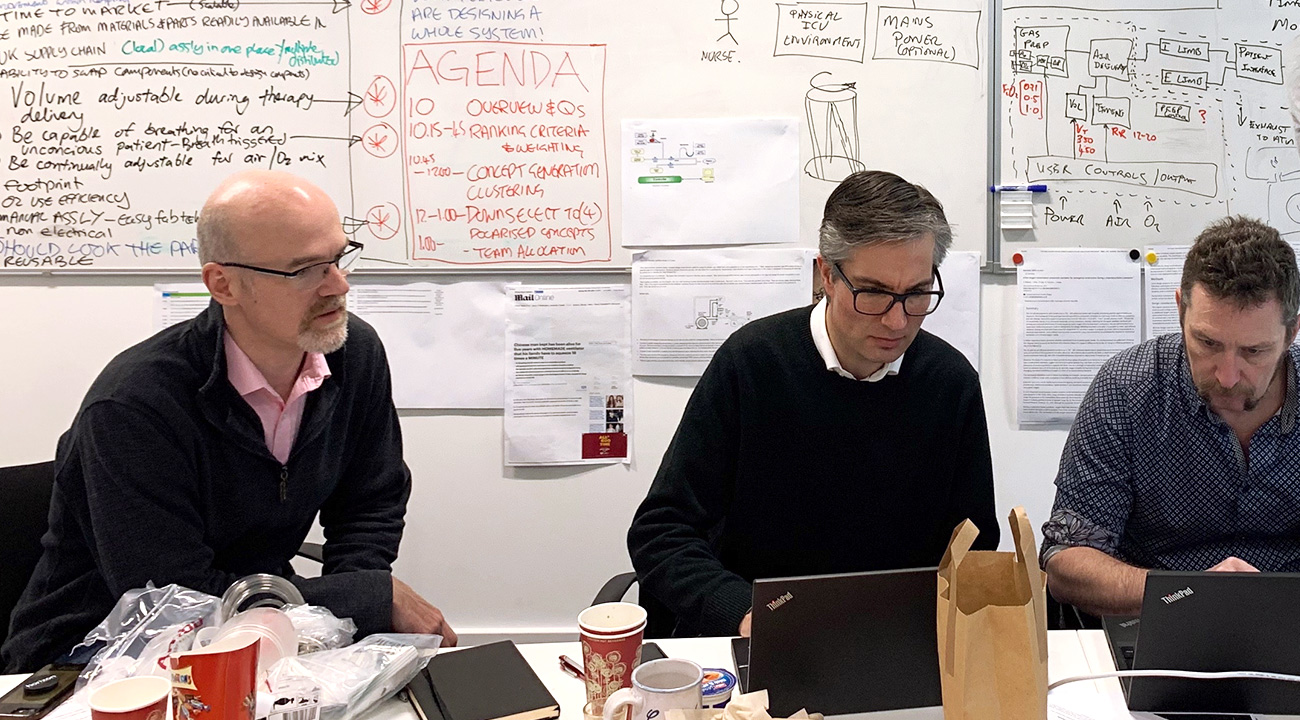

The story is characterised by collaboration – both internally and externally. The passionate and tireless response of the multidisciplinary inhouse Cambridge Consultants team was matched by productive partnerships with the regulator, clinical advisers, government representatives and manufacturing partners. We also shared insights and advice with fellow companies engaged in similar programmes.

“Veloci-Vent was a remarkable response to the Ventilator Challenge and underwent several independent function and usability tests at the Medical Devices Testing and Evaluation Centre. It met all of the essential requirements of the Rapidly Manufactured Ventilator Specifications issued by the regulator. If predictions had materialised, Veloci-Vent could have supported large numbers of critically ill patients.”

The challenge

Sprint-based approach

The clock began ticking the moment we came off the phone to the government. It would normally take several years to develop a patient-ready system to the required safety and clinical utility. We were given six weeks. With a traditional development approach we implemented an agile, sprint-based method similar to that used in consumer or industrial products.

Clinical insight

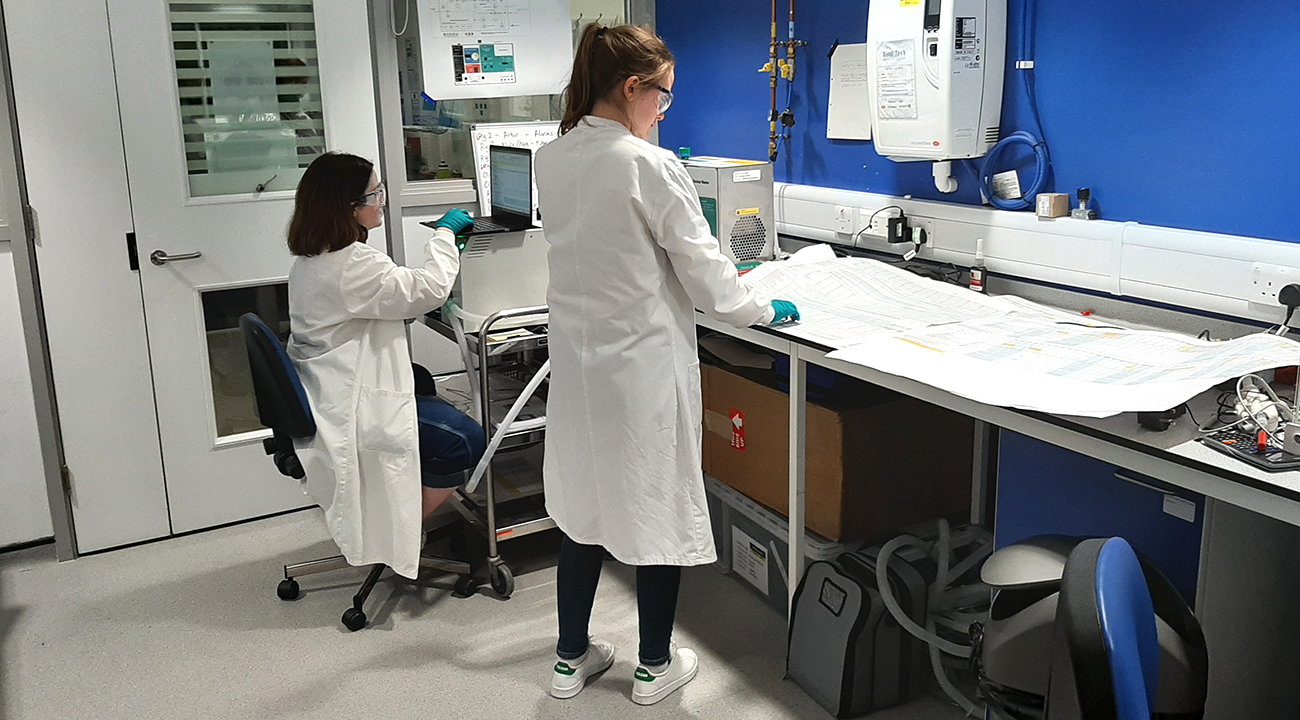

The pace was maintained by integrating continuous clinical insight into the development. Daily calls with frontline clinicians generated priceless insight and feedback.

On most days we carried out more traditional human factors and usability formative testing with the target end user group.

Challenge of change

The evolving understanding of clinical requirements to treat COVID-19 meant that the specification was evolving up to the day of submission. It was vital to keep track of changes and document them within an ISO 13485 development. Specification management infrastructure gave us the ability to respond rapidly and maintain control and traceability.

We aligned our team to a clear but flexible architecture, allowing us to adapt and maintain control. This, together with robust specification management, allowed us to delegate a huge amount of decision making into the 20 workstreams, significantly speeding up design decisions.

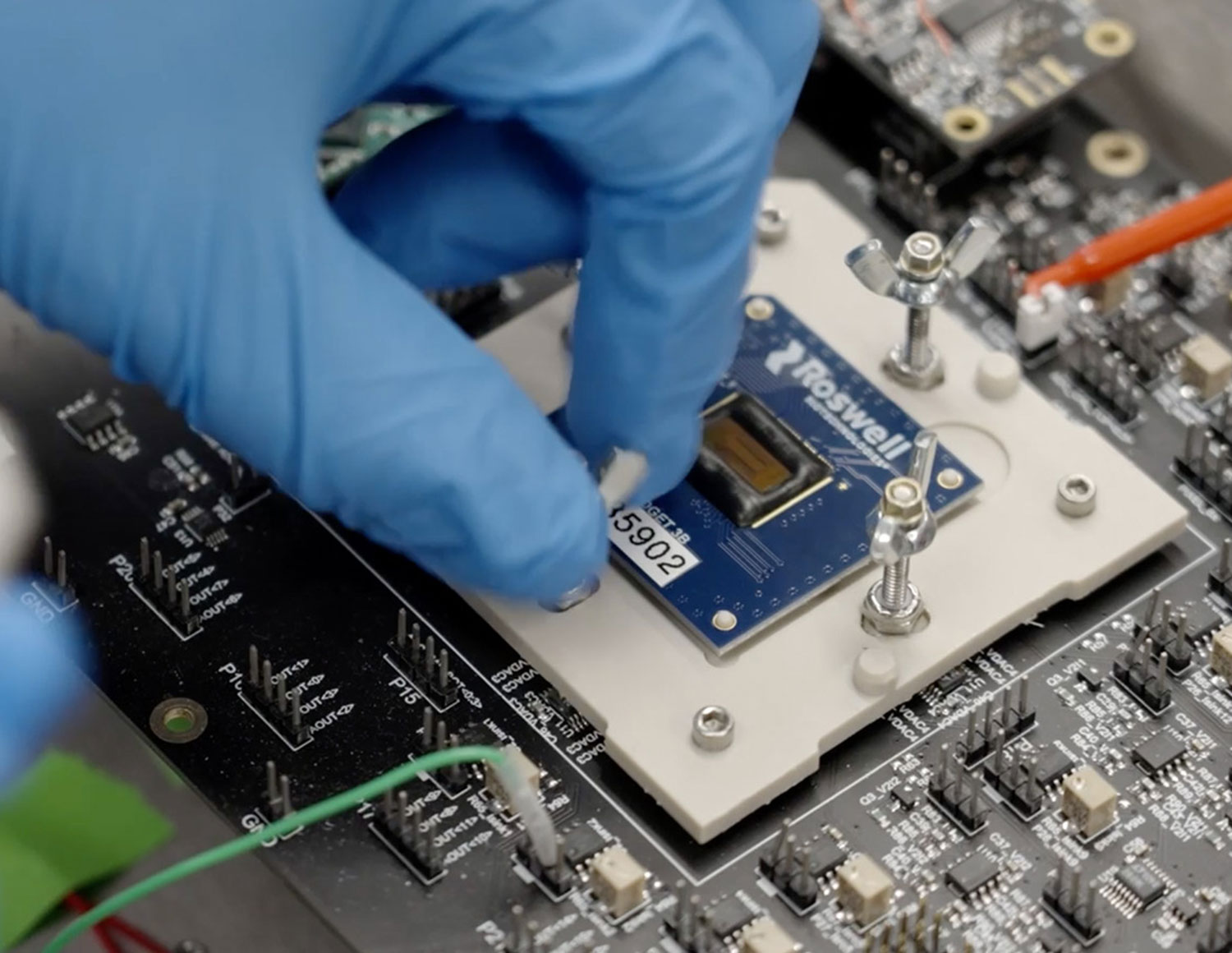

Software development

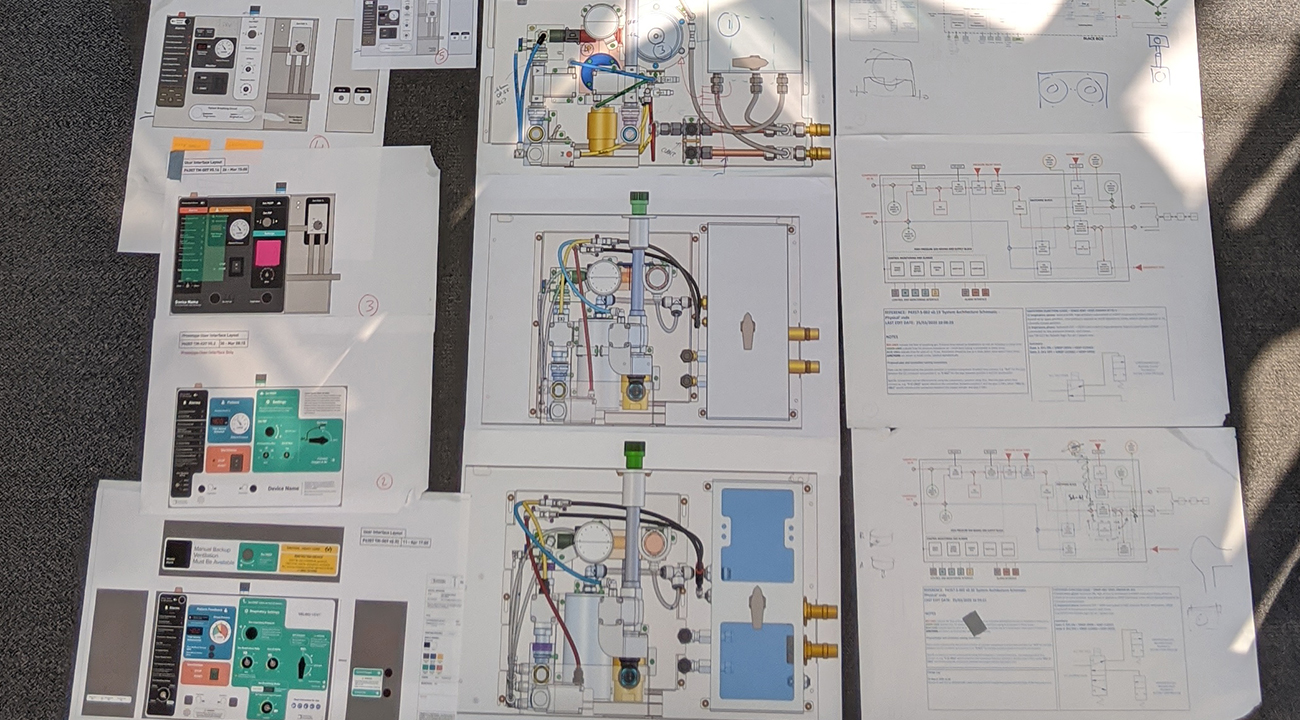

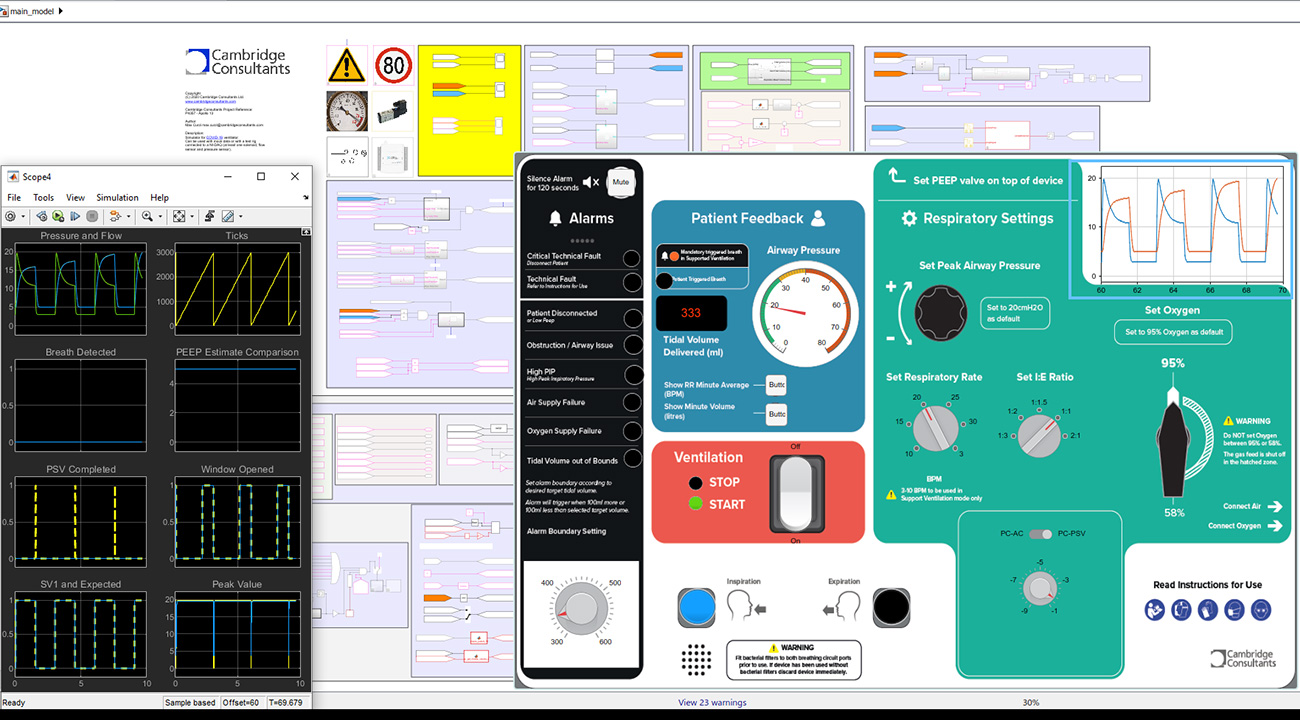

By developing software models of the system early, the team brought robustness to the design. Making heavy use of virtual modules and hardware-in-the-loop testing we developed interconnected electronics, pneumatics and software in parallel rather than in series.

Development of Class C software is an onerous process. We tightly coupled software design and test, sprinting from prototype to prototype to reflect evolving specifications. Our continuous integration server fed directly into automated test rigs, allowing code to be checked rapidly and frequently at unit, integration and system level.

“You brought pace, collaboration and innovation to this challenge, and that is recognised and appreciated across government. The commitment that you have shown has been truly inspirational.”

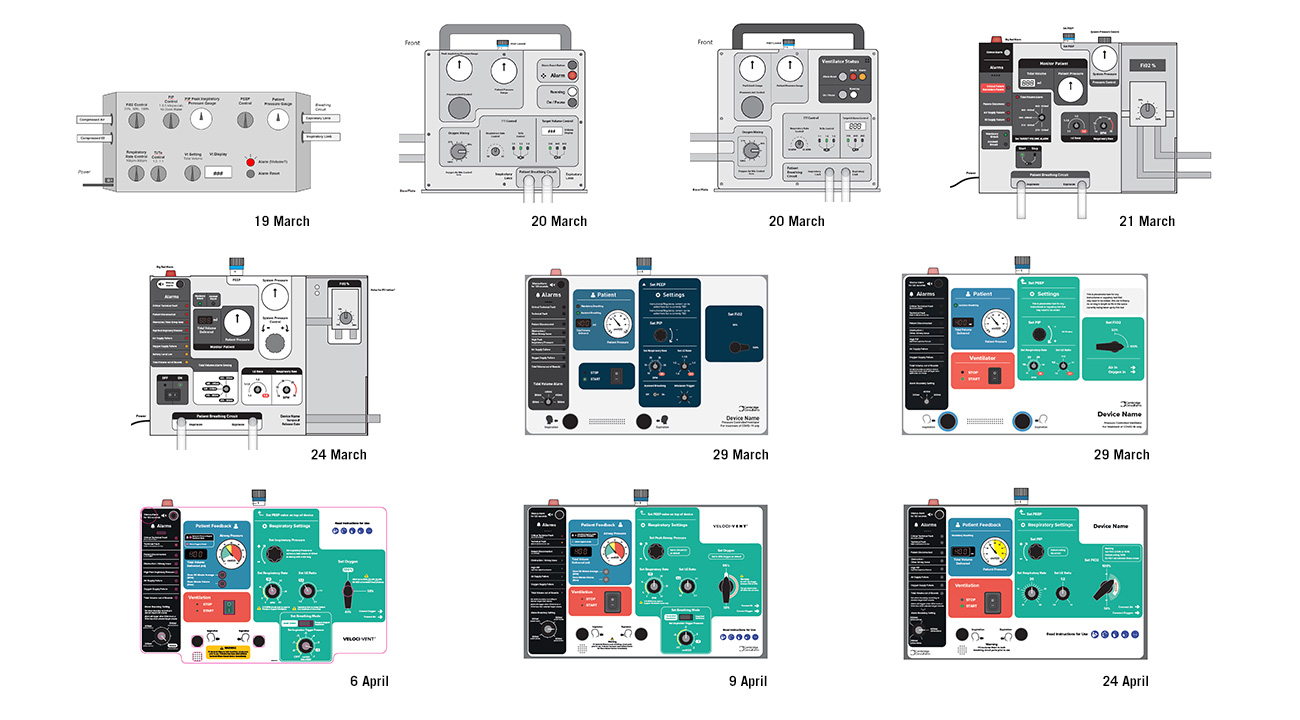

User interface iterations

The user interface evolved through over 50 iterations to accommodate layout changes and usability learnings. A vital safety aspect was organising the key inputs and outputs to present information as clearly as possible.

We collaborated with the clinical panel of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) daily and carried out almost continuous formative testing with nurses and clinicians via video conferencing to access the evolving prototypes.

Robustness and reliability

Chief among the many manufacturing challenges was the fact that because of supply chain disruption, our design had to be limited to components readily available at scale. At the outset, we made such availability a key criterion of the selection process as we evaluated a range of concepts. The chosen one used widely available pneumatic components with proven robustness and reliability.

Unparalleled ability to scale

From a standing start, the team was scaled up to 60 engineers on the Monday following the initial call and to 180 by the end of the first week.

In all, over 220 staff experienced in medical device development contributed during the project. With teams sited across the globe, tasks that started in Singapore were handed on to the UK and then the US on the same day.

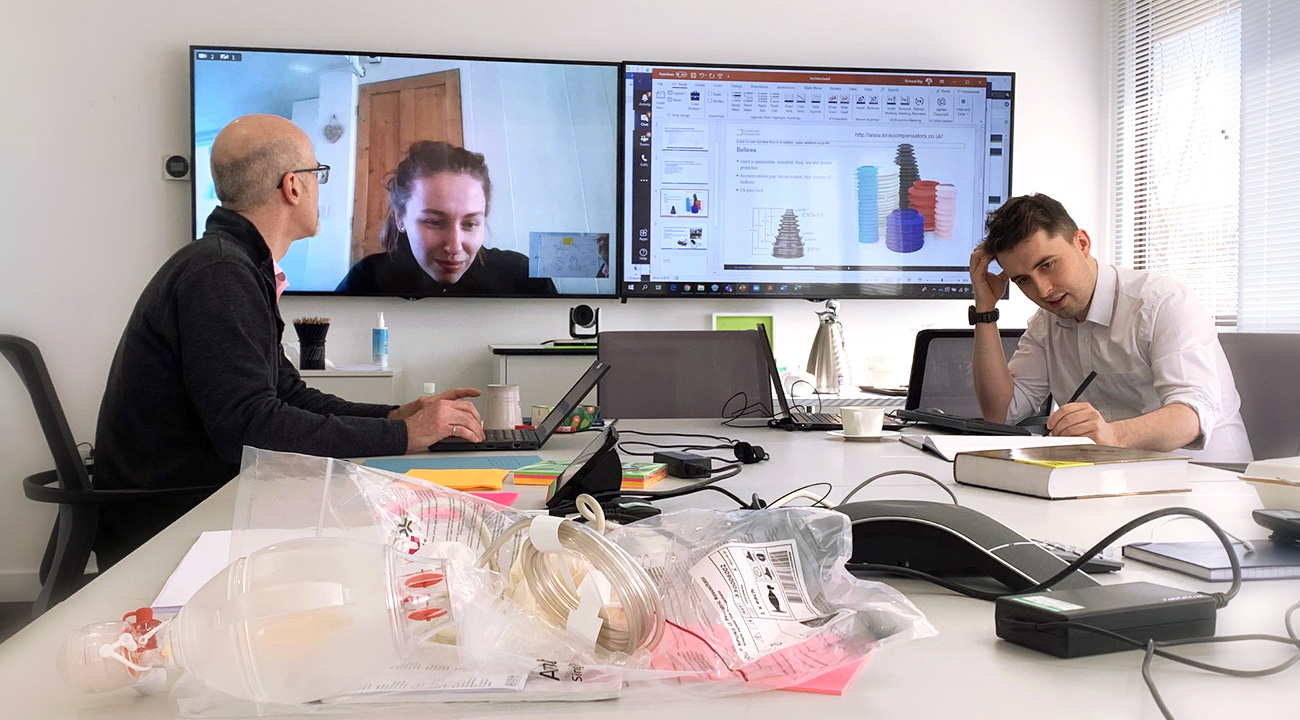

Socially distanced teamwork

This was a time of lockdown and social distancing. We organised a global team of over 200 engineers into 20 distinct workstreams with a clear understanding of where their jigsaw piece fitted into the architecture and well-defined interfaces. Workstream leaders attended daily ‘big issue’ coordination meetings, but otherwise decisions were devolved to the teams.

Most worked effectively from home, which freed up offices, labs and workshops for essential on-site work with suitable distancing measures. Many teams were geographically organised so that tasks that started in Singapore were handed on to the UK and then the US. This was a project that rocked… and rolled successfully around the world.